Born & Bred: Built to Win

By Adam Lucas, May 12, 2024

The 1976 Olympics marked the only time Dean Smith altered his coaching approach.

On exactly one occasion in his decorated career, Dean Smith coached for the sole purpose of winning.

Smith, of course, is famous for reminding his players of the billion people in China who had no idea the Tar Heels were about to play what they considered an important game. He was fiercely competitive, but he was also realistic about the greater worldwide significance of a basketball game.

But at the 1976 Olympics, he coached only for winning.

“At Carolina, we always talked about doing the best we could, and that if we did the best we could, winning would probably be the outcome,” said Phil Ford, a point guard on that team. “The Olympics was the only time that Coach Smith ever talked solely about winning. We all understood that winning was the only thing that would make that team successful.”

The United States had lost—some would say had been robbed—the 1972 gold medal after a controversial defeat to the Soviet Union. It was the first loss ever in Olympic play for the Americans, and an embarrassing setback for the nation that invented the game. Believing the gold had been stolen from them, the ’72 team (including Carolina’s Bobby Jones) voted unanimously not to accept the silver medal.

Remember, this was an era when the Olympics were as much a worldwide political stage as they were a sporting showcase. The 1972 loss wasn’t just a basketball loss. It was a major defeat, seen worldwide, at the hands of the Soviet Union. Losing another gold medal in a sport invented by the homeland would have been as damaging to the United States as the 1980 hockey loss was to the Soviet Union.

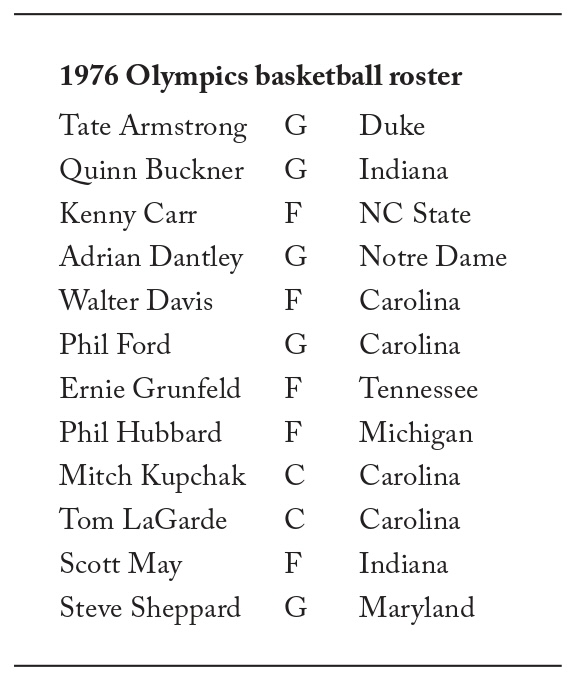

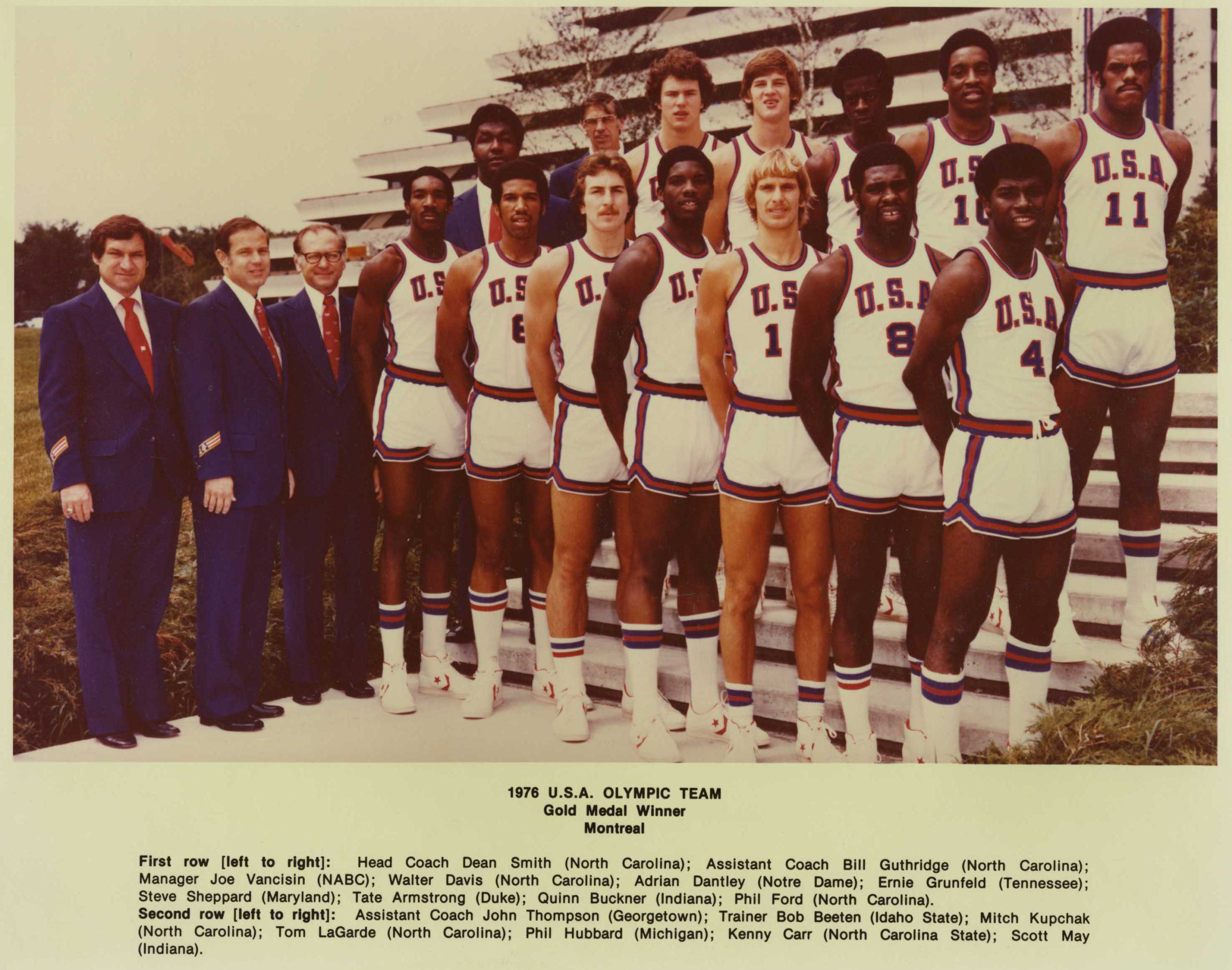

USA Basketball entrusted one man with the head coaching position for the 1976 Olympics in Montreal: Dean Smith. Their choice immediately drew some criticism when Smith selected four Tar Heels—Ford, Walter Davis, Tom LaGarde and Mitch Kupchak—along with three other Atlantic Coast Conference representatives (and a player who would turn out to be an extended member of the Carolina family, Indiana’s Scott May, whose son Sean was a member of the 2005 national champions and a current member of the Tar Heel basketball staff ). Bill Guthridge served as the team’s assistant coach.

“There were guys in that camp who ended up being better pro players than the guys who made the team,” Kupchak said. “Even in that camp, their talent stood out. So Coach Smith really rolled the dice, especially by taking four Carolina guys. We felt the pressure. So the pressure he must have felt in trying to put together that team to win the gold back must have been incredible.”

“We got a lot of negative press,” Davis said in an interview earlier this decade, “about all the ACC guys we had on the team.”

But anyone who knew Smith would have expected exactly that roster makeup. Smith’s career was built on loyalty. Of course, in the most important win-or-else scenario in his coaching career, he would want four of his own players, and three more with whom he was very familiar.

As soon as the team was assembled, players noticed a change in the head coach’s style.

“We played very much the same style that we played at Carolina, but I noticed a difference in Coach Smith’s coaching right away,” Davis said. “Everyone knew we had been cheated in ’72, and everyone was very focused on getting back the gold medal.”

On July 18, 1976, the team debuted with a 106-86 thumping of Italy. They compiled a 5-0 mark in the group round, winning fairly handily with the exception of a 95-94 escape against Puerto Rico. That game was marked by a 35-point performance from Butch Lee for Puerto Rico; he would later become even more familiar to Tar Heel fans after his outstanding showing in the 1977 national title game for Marquette.

The Soviet Union, meanwhile, was even more dominant in their group games, blitzing to a 5-0 record and outscoring their opponents by an average of 34.8 points per game. But in the knockout round, the unexpected happened: although the USA defeated Canada, 95-77, to advance to the gold medal game, the USSR was upset by Yugoslavia.

“We all felt the pressure because of 1972,” Kupchak said.

“Everybody thought we’d play the Soviet Union in the finals, but they never made it. We just assumed that’s who we would play and it was our job to bring back the gold medal. The USA-Soviet Union game was all that was being talked about.”

Leave it to Smith, then, to get his team refocused with the gold medal game taking place the very next day after the surprising result in the semifinals. The United States had waxed Yugoslavia during pool play; they did it again on July 27 in the gold medal game, taking a 95-74 victory. Kupchak scored 14 points in the gold medal victory, and Davis also saw action in the championship win.

For the summer, Adrian Dantley led the team with a 19.3 points per game scoring average. May was second at 16.7, and Kupchak and Carr were also in double figures. Ford paired his 11.3 scoring average with 9.0 assists per game. Despite all the national criticism, maybe those Carolina kids could play, after all.

To this day, Tar Heel head coach Hubert Davis warmly recalls riding around in a car in Chapel Hill with his uncle Walter and Ford as they showed off their gold medals.

“Either before or after the 1976 Olympics, I never heard Coach Smith talk about winning the way he talked about it that summer,” Ford said. “That was the only time I heard him ever talk about how important it was to win. And looking back on it, that was probably the only way to coach that team. We had a short time together and needed because winning was the only thing that would make that team successful.

“People said we weren’t old enough or tough enough to compete. But I knew our guys. I knew how tough they were. If there was someone tougher than them, I didn’t want them.”